Ultra-processed foods? Just say no

Americans love their ultra-processed foods, whether they come as cereal (like Cap’n Crunch, a favorite of mine as a kid), snack foods (like Cheetos), entr’es (like hot dogs), or desserts (like Twinkies). Sure, loading your plate with vegetables, fruits, fish, healthful oils, and grains in a Mediterranean-style diet boosts heart and brain health. But if you also eat some ultra-processed foods, is that bad for your brain health?

What to know about this new study

A new study appears to deliver resounding yes: eating ultra-processed foods is linked to a greater risk of cognitive impairment and strokes.

This well-designed observational study examined data from the REGARDS (REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke) project, a longitudinal study of non-Hispanic Black and white Americans ages 45 years and older. Study participants were initially enrolled between 2003 and 2007 and were given a number of questionnaires evaluating health, diet, exercise, body mass index, education, income, alcohol use, mood, and other factors. In addition, tests of memory and language were administered at regular intervals.

To examine the risk of stroke and cognitive impairment, data from 20,243 and 14,175 participants, respectively, were found usable based on the quality of the information from the questionnaires and tests. Approximately one-third of the sample identified as Black and the majority of the remaining two-thirds identified as white.

The results of the study

- According to the authors’ analysis, increasing the intake of ultra-processed foods by just 10% was associated with a significantly greater risk of cognitive impairment and stroke.

- Intake of unprocessed or minimally processed foods was associated with a lower risk of cognitive impairment.

- The effect of ultra-processed foods on stroke risk was greater for individuals who identified as Black compared to individuals who identified as white.

Study participants who reported following a healthy diet (like a Mediterranean, DASH, or MIND diet) and consumed minimal ultra-processed foods appeared to maintain better brain health compared to those who followed similar healthy diets but had more ultra-processed foods.

Why might ultra-processed foods be bad for your brain?

Here are some biologically plausible reasons:

- UPFs are generally composed of processed carbohydrates that are very quickly broken down into simple sugars, equivalent to eating lots of candy. These sugar loads cause spikes of insulin, which can alter normal brain cell function.

- Eating ultra-processed foods is associated with a higher risk of metabolic syndrome and obesity, well-established conditions linked to high blood pressure, abnormal blood lipid levels, and type 2 diabetes.

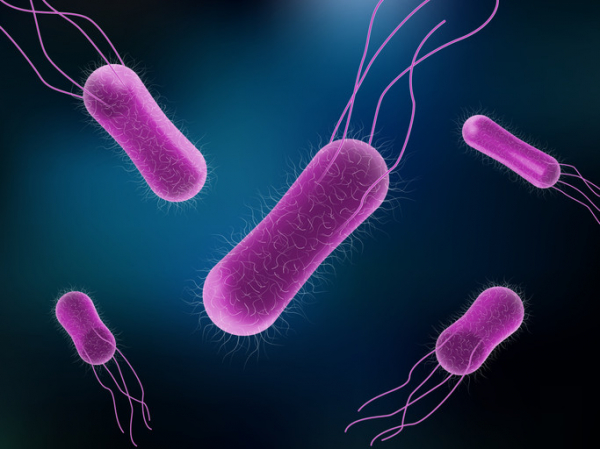

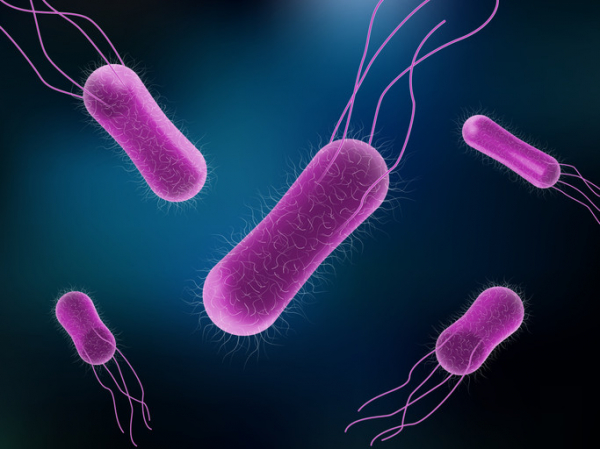

- There are unhealthy additives in ultra-processed foods to change the texture, color, sweetness, or flavor. These additives disrupt the microbiome in the gut and can lead to gut inflammation that can cause

- the production of microbiome-produced metabolites that can affect brain function (such as short-chain fatty acids and lipopolysaccharides)

- leaky gut, allowing toxins and inflammatory molecules to enter the bloodstream and go to the brain

- altered neurotransmitter function (such as serotonin) that can impact mood and cognition directly

- increased cortisol levels that mimic being under chronic stress, which can directly impact hippocampal and frontal lobe function, affecting memory and executive function performance, respectively

- an increased risk for Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and other neurodegenerative diseases due to inflammatory molecules traveling from the gut to the brain.

- Because ultra-processed foods have poor nutritional value, people will often be hungry shortly after eating them, leading to overeating and its consequences.

The take-home message

Avoid processed foods, which can include chips and other snack foods, industrial breads and pastries, packaged sweets and candy, sugar-sweetened and diet sodas, instant noodles and soups, ready-to-eat meals and frozen dinners, and processed meats such as hot dogs and bologna. Eat unprocessed or minimally processed foods, which — when combined with a healthy Mediterranean menu of foods — include fish, olive oil, avocados, whole fruits and vegetables, nuts and beans, and whole grains.

About the Author

Andrew E. Budson, MD, Contributor; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Andrew E. Budson is chief of cognitive & behavioral neurology at the Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System, lecturer in neurology at Harvard Medical School, and chair of the Science of Learning Innovation Group at the … See Full Bio View all posts by Andrew E. Budson, MD